Mark

Tarver was born too many years ago to count in

the industrial town of Manchester. One of my

early memories includes ruined houses still left

from the Blitz. I can also just remember one of

the last great smogs (a wonderful vision,

greyish-yellow like catarrh from a smoker's lungs

and thick enough to tap on the window). I wanted

to go out and play in it but was refused. This

was my introduction to the unreasonable world of

adults.

My family moved to Jersey where I grew up. I

experienced the Great Freeze of '63 and Hurricane

Betsy in '65. I wanted to go out and play with

Betsy too, but guess what happened to that idea?

My school reports showed I did what I wanted at

my own pace and showed little interest in

competition. This was thought of as a problem,

although it seems to me to be precocious wisdom.I followed in

the family tradition by being placed on school

probation (my brother was suspended). I read

philosophy at Reading University graduating in

1978 with a first and then going on to Corpus

Christi, Oxford.

The

college still sends me expensively bound

periodicals of astounding dullness detailing the

minutae of college life. The last one showed a

picture of some ancient cloth which I at first

took to be the corroded underwear of Oliver

Cromwell. Expensively bound, pretentious and

utterly dull would well describe Oxford.

|

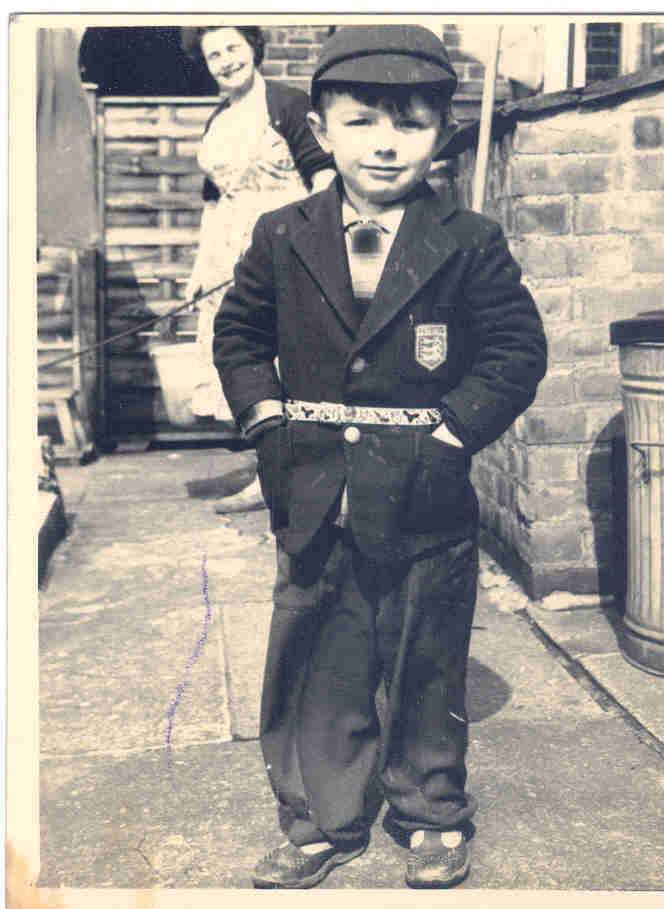

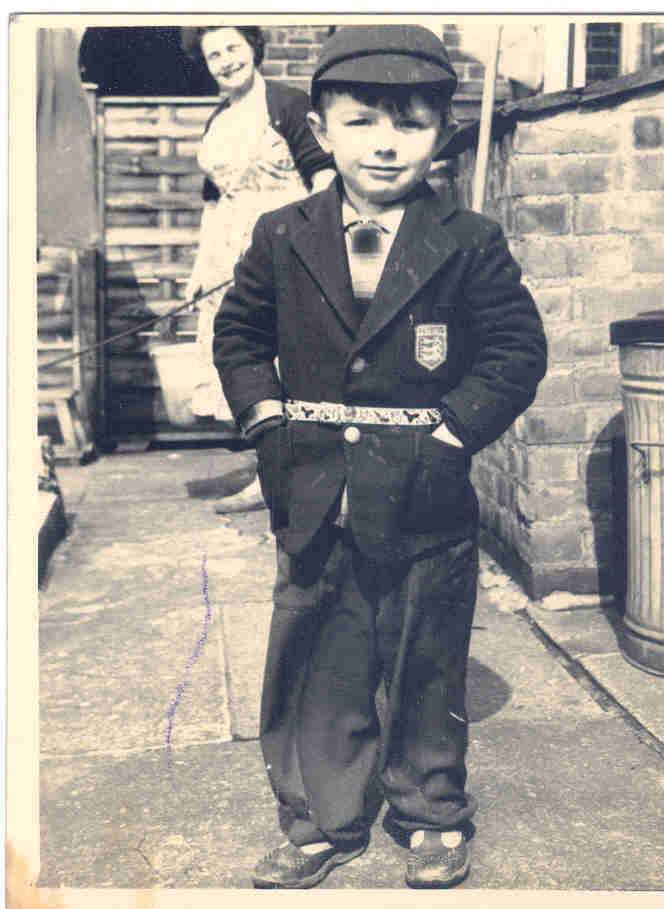

4 years old in industrial

Manchester; with the same precocious attitude and

suave dress sense that I carried into later life.

|

I took a Ph.D.

at Warwick and found my way into computing by way of the

BBC micro. It had 32 KB of main memory to play with. It

was an invitation to boldly go where no man has gone

before and I was in charge of the spaceship equivalent of

the Galileo shuttle. It was great fun. From there it was

a hop to working in a software company and then to the

philosophy department at Leeds which was investing in

computers.

I knew the location of the little red switch at the back

on the computer that turned it on. Who would have

thought? Heads were turned. I had already solved an

outstanding open problem and so I got the job. It was an

invitation to mess about for two years with computers.

There was one person in the philosophy department who was

treated with disdain. He smoked continental cigarettes

and wore NHS granny glasses mended with cellotape. His

name was Gyorgy and he was a Hungarian in exile. Gyorgy

was unpopular because he actually knew something about

computers and did not hide the fact, and because he wrote

impeccably grammatical English sentences that really

required the use of a bracket balancing editor to read

them. One famous example was his seminar abstract which

consisted of a single sentence of 200 words.

Of course Gyorgy wrote in Lisp and so I was hooked. We

competed for the attentions of the DEC-10 mainframe, a

class act who bestowed her favours impartially on both

admirers. Gyorgy was infamous in computer support for

resource-hungry Lisp programs that dimmed the lights

whenever he ran them.

They were good times and of course they could not last.

The government got wind of the fact that we weren't

actually producing anything, but enjoying ourselves and

put a stop to it. After two years of anarchy with Lisp,

in 1988 I was sent to the LFCS in Edinburgh for

correctional training in ML. Two years after that I

returned to Leeds and gave my talk on ML. The first slide

was titled

Why

is Programming in ML like Safe Sex?

Because you can't catch any bugs but it's not much fun.

But I liked the

idea of pattern-matching and borrowed this for Lisp. Thus

was taken the first step to Shen.

Leeds was fun at first and then it too got very serious.

The department took the government directives seriously

and started to turn itself into a 'centre of excellence'.

Finding myself increasingly out of step with the fuhrer

directives, I left in 1999.

Then off to America in 2002 and Stony Brook. I was an

instructor for discrete maths and given a deadly book by

a chap called Anderson as the course text. Weighing the

equivalent of bucket of lard and about as digestable, it

turned me off so much that I donated it to a grad student

and rewrote the course. We used computer-assisted proof

to learn logic and these innovations seriously annoyed

the UG committee. My resignation was a foregone

conclusion but still remains, in my view, a masterpiece

of how to napalm your bridges in style. It also contains

a plea for making computer science coherent and

interesting. From the ashes of that course was to spring

Logic, Proof and Computation.

At 56 what I've learnt from life is that if you want to

be free, you have to work at it and make sacrifices. Most

particularly you have to beware people who tell you that

true freedom is giving them your work and time for free.

Remember if you're not irritating somebody, you're not

being yourself.

copyright (c) Mark

Tarver 2025

|